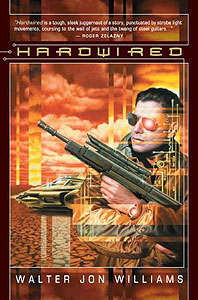

Excerpt – Hardwired

“Hardwired”® is a tough, sleek juggernaut of a story, punctuated by strobe-light movements, coursing to the wail of jets and the twang of steel guitars— glittering, nasty, and noble— and told in a style perfectly suiting its content. It has all my favorite things— blood, love, fire, hate, and a high ideal or two. I wish I’d written this one.” — Roger Zelazny.

“Hardwired”® is a tough, sleek juggernaut of a story, punctuated by strobe-light movements, coursing to the wail of jets and the twang of steel guitars— glittering, nasty, and noble— and told in a style perfectly suiting its content. It has all my favorite things— blood, love, fire, hate, and a high ideal or two. I wish I’d written this one.” — Roger Zelazny.

“Williams’ use of language is as explosive and as techno tinged as the world he describes. Reading the book is like taking a jet ride across a futuristic America, with acceleration forcing you back in your seat all the way.” Tom Von MalderText copyright (c) 1997 by Walter Jon Williams. It may not be reproduced in any form without permission of the author.

This is an excerpt from my novel “Hardwired”, published in 1986 by Tor Books. A shorter version of this excerpt was published in Omni magazine. This excerpt is copyright (c) 1986 by Walter Jon Williams. All rights are reserved by the author. It may not be duplicated or distributed without permission of the author.

“Due to strong language and themes,” as they say on TV, this excerpt should be viewed only by adults — of all ages.

TODAY/YES

Bodies and parts of bodies flare and die in laserlight, here the translucent sheen of eyes rimmed in kohl or turned up to a heaven masked by the starry-glitter ceiling, here electric hair flaring with fashionable static discharges, here a blue-white glow of teeth rimmed in darkglow fire and pierced by mute extended tongue. It is zonedance. Though the band is loud and sweat-hot many of the zoned are tuned to their own music, hearing sounds of their choice through chips wired delicately to the auditory nerves, or dancing to the headsets through which they can pick up any of the bar’s twelve channels . . . they seeth in arthrhythmic patterns, heedless of each other. Perfect control is sought, but there are accidents— impacts— a flurry of fists and elbows— and someone crawls out of the zone, whimpering through a bloodstreaked hand, unnoticed by the pack.

To Sarah the dancers at the Aujourd’Oui seem a twitching mass of dying flesh, bloody, insensate, mortal. Bound by the mud of Earth. They are meat. She is hunting, and Weasel is the name of her friend.

MODERNBODYMODERNBODYMODERNBODYMODERN

ALL ELECTRIC — REPLACEABLE — IN THE MODE!

GET ONE NOW!

BODYMODERNBODYMODERNBODYMODERNBODY

The body designer has eyes of glittering violet above cheekbones of sculptured ivory. Her hair is a streaky blonde that sweeps to an architecturally perfect dorsal fin behind her nape. Her muscles are catlike and her mouth is a cruel flower.

“Hair shorter, yes,” she says. “One doesn’t wear it long in freefall.” Her fingers lash out and seize Sarah by the chin, tilting her head to the cold north light. Her fingernails are violet, to match her eyes, and sharp. Sarah glares at her, sullen. The body designer smiles. “A little pad in the chin, yes,” she says. “You need a stronger chin. The tip of the nose can be altered; you’re a bit too retrouss. The curve of the jawbone needs a little flattening— I’ll bring my paring knife tomorrow. And of course we’ll remove the scars. Those scars have got to go.” Sarah curls her lip under the pressure of the violet-tipped fingers.

The designer drops Sarah’s chin and whirls. “Must we use this girl, Cunningham?” she asks. “She has no style at all. She can’t walk gracefully. Her body’s too big, too awkward. She’s nothing. She’s dirt. Common.”

Cunningham sits silently in his brown suit, his neutral, unmemorable face giving away nothing. His voice is whispery, calm, yet still authoritative. So devoid is it of highlights that Sarah thinks it could be a computer voice. “Our Sarah has style, Firebud,” he says. “Style and discipline. You are to give it form, to fashion it. Her style must be a weapon, a shaped charge. You will make it, I will point it. And Sarah will punch a hole right where we intend she should.” He looks at Sarah with his steady brown eyes. “Won’t you, Sarah?” he asks.

Sarah does not reply. Instead she looks up at the body designer, drawing back her lips, showing teeth. “Let me hunt you some night, Firebud,” she says. “I’ll show you style.”

The designer rolls her eyes. “Dirtgirl stuff,” she snorts, but she takes a step back. Sarah grins.

“And Firebud,” Cunningham says. “Leave the scars alone. They will speak to our Princess. Of this cruel terrestrial reality which she helped create. Which she dominates. With which she is already half in love.

“Yes,” he says, “leave the scars alone.” For the first time he smiles, a brief tightening of the cheek muscles, cold as liquid nitrogen. “Our Princess will love the scars,” he says. “Love them till the very last.”

WINNERS/YES LOSERS/YES

The Aujourd’Oui is a jockey bar, and they are all here, moonjocks and rigjocks, holdjocks and powerjocks and rockjocks— the jocks condescending to share the floor along with the mudboys and dirtgirls who surround them, those who hope to become them or who love them or want simply to be near them, to touch them in the zonedance and absorb a piece of their radiance. The jocks wear their colors, vests and jackets bearing the emblems of their blocs, TRW, Pfizer, Toshiba, Tupolev, ARAMCO, blazons of the Rock War victors borne with careless pride by the jocks who had won their place in the sky. Sarah stalks among them in a black satin jacket, blazoned on its back with a white crane that rises to the starry firmament amid a flock of chromebright Chinese characters. It is the badge of a small bloc that does most of its business in Singapore, and is hardly ever to be seen here in the Florida Free Zone. Her face is unknown to the regulars but it is hoped they won’t think it odd, not as odd as it would seem if she wore the badge of Tupolev or Kikuyu Optics I.G.

Her sculpted face is pale, the Florida tan gone, her eyes black-rimmed. Her almost-black hair is short on the sides and brushy on top, her napehair falling in two thin braids to the small of her back. Chrome steel earrings brush her shoulders. Firebud has broadened her already-broad shoulders and pared down the width of her pelvis; her face is sharp and pointed beneath a widows’s peak, looking like a succession of arrowheads, the shaped-charge that Cunningham demands. She wears black dancing slippers laced over the ankles and dark purple stretch-overalls with suspenders that frame her breasts, stretching the fabric over the nipples that Firebud has made more prominent. Her shirt is gauze spangled silver, her neckscarf black silk. There is a 2-way spliced into her auditory nerve and a receiver tagged to the optic centers of her forebrain, monitoring police broadcasts at the moment, a constant Times Square of an LED running amber, at will, above her expanded vision.

Gifts from Cunningham. Her wired-up nerves are her own.

So is Weasel.

I LOVE MY KIKUYU EYES, SEZ PRIMO PORNOSTAR ROD MCLEISH, AND WITH THE INFRARED OPTION, I CAN TELL IF MY PARTNER’S REALLY EXCITED OR IF I’M JUST ON A SILICON RIDE . . . KIKUYU OPTICS I.G., A DIVISION OF MIKOYAN-GUREVICH

She met Cunningham in another bar, the Blue Silk. Sarah ran Weasel as per contract but the snagboy, a runner who had got more greedy than he had the smarts to handle, had been altered himself and she is nursing bruises. She recovered the goods, fortunately, and since she the contract was with the thirdmen she has been paid in endorphins, handy since she’s had to use a few of them herself. There is a bone bruise on the back of her thigh and she can’t sit; instead she leans back against the padded bar and sips her rum and lime. The Blue Silk’s audio system plays island music and sooths her played-up nerves.

The Blue Silk is run by an ex-cutterjock named Maurice. He is a West Indian with the old-model Zeiss eyes who was on the losing side in the Rock War. There are pictures of his friends and heroes on the walls, all of them with the azure silk neck scarves of the elite space defense corps, most of them framed with black mourning ribbons that are turning purple with the long years.

Sarah wonders what he has seen with those eyes. Has it included the burst of X-rays that preceded the ten thousand-ton rocks, launched from the Orbital mass drivers, that tore through the atmosphere to crash on Earth’s cities? The artificial meteors, each with the force of a nuclear blast, had first fallen in the Eastern hemisphere, over Mombasa and Calcutta, and by the time the planet had rotated and made the western hemisphere a target the Earth had surrendered— but the Orbital blocs felt they hadn’t made their point forcefully enough in the West, and so the rocks fell anyway. Communications foulup, they said.

Earth’s billions knew better.

Sarah was eight. She was doing a tour in a Youth Reclamation Camp near Stone Mountain when three rocks obliterated Atlanta and killed her mother. Daud, who was five, was trapped in the rubble, but the neighbors heard his screams and got him out. After that Sarah and her brother bounced from one DP agency to another, then ended up in Tampa with her father, who she hadn’t seen or heard from since she was three. The social worker held her hand all the way up the decaying apartment stairs, and Sarah held Daud’s. She remembered the way the halls stank of urine, and the way a dismembered doll lay strewn on the second-floor landing. When the door opened she saw a man in a torn shirt with sweat stains in the armpits. He had watery alcoholic eyes. The eyes, uncomprehending, had moved from Sarah and Daud and then to the social worker as the papers were served, and the social worker said, “This is your father. He’ll take care of you,” before dropping Sarah’s hand. It turned out to be only half a lie.

She looks at the fading photographs in their dusty frames, the dead men and women with their metallic Zeiss eyes. Maurice is looking at them, too. He is lost in his memories, and it looks as if he is trying to cry; but his eyes are lubricated with silicon and his tear ducts are gone, of course, along with his dreams, with the dreams of the billions who had hoped the orbitals would improve their lives, who have no hope now but to get out somehow, out into the cold, perfect cobalt of the sky.

Sarah wishes she could cry herself, for the dead hope framed in black on the walls, for herself and Daud, for the broken thing that was all earthly aspiration, even for the snagboy who had seen his chance to escape but not been smart enough to play his way out of the game his hopes had dealt him into. But the tears are long gone and in their place is hardened steel desire— the desire shared by all the dirtgirls and mudboys. To achieve it she has to want it more, and she has to be willing to do what is necessary— or to have it done to her, if it came to that. Involuntarily her hand comes to her throat as she thinks of Weasel. No, there is no time for tears.

“Looking for work, Sarah?” The voice came from the quiet white man who has been sitting at the end of the bar. He has come closer, one hand on the back of the bar stool next to her. He is smiling as if he is unaccustomed to it.

She narrows her eyes as she looks at him sidelong, and takes a deliberately long drink. “Not the kind of work you have in mind, collarboy,” she says.

“You come recommended,” he says. His voice is sandpaper, the kind you never forget. Perhaps he’d never had to raise it in his life.

She drinks again and looks at him. “By whom?” she says.

The smile is gone now; the nondescript face looks at her warily. “The Hetman,” he says.

“Michael?” she asks. He nods.

“My name is Cunningham,” he says.

“Do you mind if I call Michael and ask him?” she says. The Hetman controls the Bay thirdmen and sometimes she runs the Weasel for him. She doesn’t like the idea of his dropping her name to strangers.

“If you like,” Cunningham says. “But I’d like to talk to you about work first.”

“This isn’t the bar I go to for work,” she says. “See me in the Plastic Girl, at ten.”

“This isn’t the sort of offer that can wait.”

Sarah turns her back to him and looks into Maurice’s metal eyes. “This man,” she says, “is bothering me.”

Maurice’s face does not change expression. “You best leave,” he says to Cunningham.

Sarah, not looking at Cunningham, receives from the corner of her eye an impression of a spring uncoiling. Cunningham seems taller than he has a moment ago.

“Do I get to finish my drink first?” he asks.

Maurice, without looking down, reaches into the till and flicks bills on the dark surface of the bar. “Drink’s on the house. Outa my place.”

Cunningham says nothing, just gazes for a calm moment into the unblinking metal eyes. “Townsend,” Maurice says, a code word and the name of the general who had once led him up against the orbitals and their burning defensive energies. The Blue Silk’s hardware voiceprints him and recognizes his West Indian accents, and then the defensive systems appear from where they are hidden above the bar mirror and lock down into place. Sarah glances up. Military lasers, she thinks, scrounged on the black market, or maybe from Maurice’s old cutter. She wonders if the bar has power enough to use them, or whether they are bluff.

Cunningham stands still for another half-second, then turns and leaves the Blue Silk without a word. Sarah does not watch him go.

“Thanks, Maurice,” she says.

Maurice forces a sad smile. “Hell, lady,” he says. “You regular customer. And that fella been orbital.”

Sarah contemplates her surprise. “He’s from the blocs?” she asks. “You’re sure?”

“Innes,” Maurice says, another name from the past, and the lasers slot up into place. His hands flicker out to take the money from the bar. “I didn’t say he’s from the blocs, Sarah,” he says, “but he’s been there. Recently, too. You can tell from the way they walk, if you got the eyes.” He raises a gnarled finger to his head. “His ear, you know? It take a while to adjust. Centrifugal gravity is different from the real.”

Sarah frowns. What kind of job is the man offering? Something important enough to bring him down through the atmosphere, to hire some dirtgirl and her Weasel? It doesn’t seem likely.

Well. She’ll see him in the Plastic Girl. Or not. She isn’t going to worry about it. She shifts her weight from one leg to the other, the muscles crackling with pain even through the endorphin haze. She holds out her glass. “Another, please, Maurice,” she says.

With a slow grace that must have served him well in the high black starry evernight, Maurice turns toward the mirror and reaches for the rum. Even in a gesture this simple, there is still a throb of sadness.

ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE LOSES PATERNITY SUIT “MY LITTLE ANDROID HAS A NAME,” SOBS GRATEFUL MOTHER

KOROLEV I.G. OFFERS NO COMMENT

She takes a taxi home from the Blue Silk, trying to ignore Cunningham’s calm eyes on the back of her head as she gives the driver her address. How much is she throwing away, here?

Cunningham is across the street under an awning, pretending to read a magazine while the noonday heat and the swamping humidity bring sweat up onto his face, dripping from his nose and brow ridges onto the slick paper. She doesn’t turn to see if he registers dismay at her retreat, but somehow she doubts his expression has changed.

With Daud she shares a two-room apartment that hums. There is the hum of the coolers and recyclers, more humming from the little glowing robots that move about randomly, doing the dusting and polishing, devouring insects and arachnids and cleaning the cobwebs out of corners.

She has a modest comp deck in the front room and Daud has a vast audio system hooked to it, with a six-foot screen to show the vid. It’s on now, silently, showing computer-generated color patterns, broadcasting them with laser optics on the ceiling and walls. The computer is running the changes on red and the walls burn with cold and silent fire.

Sarah turns off the vid and looks down at the comp deck cooling, the reds fading slowly from her retinas. The endorphins are wearing off and the bone bruise on her thigh is hammering her with every step. It’s time for another dose.

She looks in her hiding place and sees that two of her twelve vials of endorphin are gone. Daud, of course. She hadn’t thought he’d find her new place so soon. Not that there are very many places to hide even small amounts of stuff in an apartment this size. She sighs, then ties her tourniquet above the elbow. She slots a vial into her injector, dials the dose she wants, and presses the injector to her arm. The injector hums and she sees a bubble rise in the vial. Then there is a warning light on the injector and she feels a tug of flesh as the needle slides on its cool spray of anaesthetic into her arm to find its vein. She unties the tourniquet, watches the LED on the injector pulse ten times, and then she feels a veil slide between her and her pain. She takes a ragged breath, then stands. She leaves the endorphins on the sofa and walks back to the comp.

Michael the Hetman is in his office when she calls. She speaks to him in Spanglish and he laughs.

“I thought I’d hear from you today, mi hermana,” he says.

“Yes?” she asks. “You know this orbiter Cunningham?”

“So-so. We’ve done business. He has the highest recommendations.”

“Whose?”

“The highest,” he says.

“So you recommend that I trust him?” Sarah asks.

His laugh seems a little jangled. She wonders if he is high. “I never make that kind of recommendation, mi hermana,” he says.

“Yes, you would, Hetman,” Sarah says. “If you are getting a piece of whatever it is Cunningham is doing. As it is, you’re just doing him a favor.”

“Do svidaniya, my sister,” says Michael, sounding annoyed, and snaps off. Sarah looks into the humming receiver and frowns.

The door opens behind her and she spins and goes into her stance, balanced to jump forward or back, cursing the endorphins that have slackened her nerves. Daud walks carelessly in the door. Behind him, carrying a six-pack of beer, comes his manager, Jackstraw, a small young man with unquiet eyes.

Daud looks up at her. “You expecting someone else?” he asks.

She relaxes. “No,” she says. “Just nerves. It’s been a nervous day.”

Daud’s eyes move restlessly over the small apartment. He has altered them from brown to a pale blue, just as he’d altered the color of his hair, eyebrows, and lashes to a white blonde. He is tanned and has his hair shoulder-length and shaggy. He wears tooled leather sandals and a tight white pair of slacks under a dark net shirt. He is taking hormone suppressants and though he is twenty he looks fifteen and beardless.

Sarah moves over to him and kisses him hello. “I’m working tonight,” he says. He gives a shadowy grin. “He wants to have dinner, I can’t stay long.”

“Is it someone you know?” she asks.

“Yes.” He gives a shadowy grin, meant to be reassuring. His blue eyes flicker. “I’ve been with him before.”

“Not a thatch?”

He shrugs out of her embrace and goes to sit on the sofa. “No,” he mumbles. “An old guy. Lonely, I guess. Easy to please. Wants to talk more than anything.” He sees the plastic pack of endorphins and picks it up, searching through it. Sarah sees two more vials vanish between his fingers.

“Daud,” she says, her voice a warning. “That’s our food and rent— I’ve got to get it on the street.”

“Just one,” Daud says. He drops the other back in the bag, holds up the other to let her see it.

“You’ve already had your share,” Sarah says.

His pale eyes flicker in his dark face. “Okay,” he says. “Uno pinchazo, hey.”

His need is too strong. She looks down and shakes her head. “One,” she agrees. “Okay.” She watches as he loads the injector and dials the dosage— a high dosage, she knows, since he only has the one. She resists the urge to check the injector, knowing that someday if he goes on this way he’ll put himself in a coma, but knowing how much he’d resent her concern. Sarah watches as the endorphin hits his head, as he lies back and sighs, his twitchy nervousness gone.

She takes the injector and frees the vial, then puts it in the plastic bag. There is a half-smile on Daud’s face as he looks up at her. “Thanks, Sarah,” he says.

“I love you,” she says.

He closes his eyes and strops his back on the sofa like a cat. His throat makes strange whimpering noises. She takes the bag and walks into her room and throws the bag on her bed. A wave of sadness whispers through her veins like a drug of melancholy. Daud will die before long, and she can’t stop it.

Once it had been Sarah who stood between him and life, now it is the endorphins that keep him insulated from the things that want to touch him. Their father had been crazy and violent and Sarah had fought him as long as she could stand it. Half her scars were Daud’s by right: she had suffered them on his behalf, shielding him with her body. The madman’s beatings had taught her to fight back, had made her hard and quick, but she couldn’t be there all the time and the old man had sensed weakness in Daud and found it. She herself hadn’t been able to stand it, and when she was fourteen she’d run with the first boy who’d promised her a place free from pain: two years later, when she’d bought her way out of her first contract and come back for him, Daud had been shattered beyond repair, the needle already in his arm. She’d led him to the new house where she worked— it was the only place she had— and there he’d learned to earn his living, as she had learned in her own time. He is broken still, and Sarah knows that as long as they are in the streets there is no way of healing him.

If she hadn’t cracked, if she hadn’t run away, she might have been able to protect him. She won’t crack again.

She returns to the other room and sees Daud lying on the sofa, one sandal hanging with the straps tangled between his toes. Jackstraw is sitting next to him on the sofa and drinking one of his beers. He glances up.

“You look like you’re limping,” he says. “Would you like me to rub your legs?”

“No,” Sarah says quickly, and then realizes she is being too sharp. “No,” she says again, with a smile. “Thank you. But it’s a bone bruise. If you touched me I’d scream.”

ARTIFICIAL DREAMS

The Plastic Girl is a hustler’s idea of the good life: plush and chrome and a lot of dark booths in the back where business can be done. There is a room for zonedance, and there are headsets that plug you into euphoric states or pornography or whatever it is you need and are afraid to shoot into your veins. Orbital pharmaceutical companies provide the effects free, as advertising for their products. There are dancers on a mirrored bar in the back, a bar equipped with arcade games so that if you win, a connection snaps in one of the dancer’s garments and it falls off. If you win big all the clothes fall off all the dancers at once.

Sarah is in the big front room: brassy music, red leather booths, brass ornaments. She does not, and will probably never, rate the quiet room in the back, all brushed aluminum the dark wood that might have been the last mahogany tree in Southeast Asia— that room is for the big boys who run this fast and dangerous world, and though there isn’t a sign that says NO WOMEN ALLOWED there might as well be. Sarah is an independent contractor and rates a certain amount of respect, but in the end she is still meat for hire, though on a more elevated plane than once she was.

But still, the red room is nice. There are colorful holograms, colors and helixes like modelled DNA, floating just above eye level, casting their variegated light through the crystal and sparkling liquor held in the patrons’ hands, and there are sockets at every table for comp decks so that the patrons can keep up with their portfolios, and there are girls with reconstructed breasts and faces who come to each table in their tight plastic corsets, bring you your drink, and watch with identical and very white smiles as you put your credit spike into their tabulator and tap in a generous tip with your fingernail.

Sarah is ready for the meet with Cunningham, wearing a navy blue jacket guaranteed to protect her against kinetic violence of up to 900 foot-pounds per square inch and trousers good for 750. She has invested some of the endorphins and bought the time of a pair of her peers. They are walking loose about the bar, ready to keep Cunningham or his friends off her back if she needs it. She knows she needs a clear head and has kept the endorphin dose down. Pain is making her edgy, and she still can’t sit. She stands at a small table and sips her rum and lime, waiting.

And then Cunningham is there, looking much as he was before, and is to be later. Bland face, brown eyes, brown hair, brown suit. A whispery voice that speaks of clean places she has never been, places bright and soft against the black and pure diamond. A body that she had once thought of as a coiled spring, but which later she comes to think of as a precision weapon with a bullet up the spout and the safety lever, just barely, holding back the firing pin.

“Okay, Cunningham,” she says. “Business.”

Cunningham’s eyes flicker to the mirror behind her. “Friends?” he asks.

“I don’t know you.”

“You’ve called the Hetman?” She nods.

“He was complimentary,” she says, “but you’re not working for him, he’s paying you a favor, maybe. So I’m cautious.”

“Understandable.” He takes a comp deck out of an inner pocket and plugs it into the table. A pale amber screen in the depths of the dark tabletop lights up, displaying a row of figures.

“We’re offering you this in dollars,” he says. Sarah feels a touch of metal on her nerves, on her tongue. The score, she thinks, the real thing.

“Dollars?” she says automatically. “Get serious.”

“Gold?” Another set of figures appears. She takes a sip of rum.

“Too heavy.”

“Stock. Or drugs. Take your pick.”

“What kind of stock? What kind of drugs?”

“Your choice.”

“Polymyxin-phenildorphin Nu. There’s a shortage right now.”

Cunningham frowns. “If you like. But there’ll be a lot of it coming onto the market in another three weeks or so.”

Her eyes challenge him. “Did you bring it down from orbit with you?” she asks.

His face fails so much as to twitch. “No,” he says. “But if I were you I’d try Chloramphenildorphin. Pfizer is arranging an artificial scarcity that will last several months. Here are the figures. Pharmacological quality, fresh from orbit.”

Sarah looks at the glowing amber numbers and nods. “Satisfactory,” she says. “Half in advance.”

“Ten percent now,” Cunningham says. “Thirty on completion of training. The rest on completion of the contract, whether you succeed or not.”

She looks up at one of the bar’s moving holograms, the colors clean and bright, as pure as if seen through a vacuum. A vacuum, she thinks. The stock offer isn’t bad, but she can do more with the drugs. Cunningham is offering her the drugs at their Orbital value, where they are made and where the cost is almost nothing. The street value is far more, and with it she can buy more stock than the amount they;re offering. Ten per cent of that figure is more than she’d made last night, when she’d gone after the snagboy.

To get into the Orbitals you have to have skills they need, skills she can never acquire. There is another way: they can’t refuse someone who owned enough shares. They are sucking up all Earth’s remaining wealth, and if you help them and buy up enough stock they might free you from the mud forever. This is almost enough, she calculates. Almost enough for a pair of tickets to the top of the gravity well.

She brings her drink to her lips. “Let’s say a quarter now,” she says. “And then I’ll let you buy me a drink, and you can tell me just what you want me to do to earn it.”

Cunningham turns and signals to one of the smiling corset girls. “It’s very simple,” he says, and he looks at her with his ice-cold eyes. “We want you to make someone fall in love with you. Just for a night.”

IS YOUR LOVER LOOKING FOR SOMEONE YOUNGER?

YOU CAN BE THAT SOMEONE!

“The Princess is about eighty years old,” Cunningham says. The hologram he gives Sarah is of a pale blonde girl of about twenty, dressed in a kind of ruffled blouse that exposes her rounded shoulders, the hollows of her clavicles. She has Daud’s watery blue eyes and freckles above her breasts. She projects an air of vulnerable innocence.

“We think he was originally from Russia,” Cunningham goes on, “but the Korolev Bureau has always been secretive and we don’t have a complete list of their senior staff and designers. When he rated the new body he asked to be a woman. He’s important enough so that they gave it to him, but they gave him a demotion— they rotate out all their old people to make way for the new. She’s doing courier duty now.”

Not unusual, Sarah thinks. These days you can get pornography read straight into the brain, plenty of chances to sample whatever pleasures you like and then, if rich enough, getting yourself a new body to suit your tastes. But the technology of personality transfer is imperfect— sometimes bits get left behind, memories, abilities, traits that might be useful. A progression of bodies can mean progressive senility. If you get a new body and aren’t so powerful you can’t be moved, you often get demoted until you can prove yourself.

“What’s her new name?” she asks.

“She’ll tell you, I’m sure. Let’s just call her Princess for now.” Sarah shrugs. There are half a dozen imbecilic security rules in this operation, and she guesses that most of them are simply to test her capacity for obedience.

“Her new body doesn’t seem to have altered her sexual orientation, just his manner of expressing it,” Cunningham says. “Princess has exhibited some characteristic behaviors since she’s started her new job. When she’s on the ground she likes to go slumming. Find herself a working girl— sometimes a dirtgirl, most often a girljock— and take her home for a night or two. She wants a pet, but a dangerous one. Not too clean. A little rough. Not too removed from the street. But civilized enough to know how to please. Not a thatch.”

“That’s me?” Sarah asks, with no surprise. “Her new pet?”

“We’ve researched you. You were a licensed prostitute for five years. And rated highly by your employers.”

“Five and a half,” she says. “And not with girls.”

“He’s a man, really. An old man. Why should it be hard for you?”

Sarah looks at the blonde freckled girl in the hologram, trying to find the old Russian in those eyes. The look that was always the same, wanting her to be some piece of private fantasy, real but not too real, orgasms genuine but never with genuine passion. The Plastic Girl, an object for things that grew hidden in their minds, something they could get rid of quickly and never have to take home. They were upset, somehow, if you didn’t understand their fantasy right away. After a while she had got so that she could.

She looks at the picture. No different from all the other old men, she thinks. Not really. Power they want, over their own flesh and another’s. Pay not so much for sex, but for power over sex, over the thing that threatens to control them. And so they take their passion and use it to control others. She understood control all right.

She looks up at Cunningham. “Did they give you a new body as well?” she asks. “Guaranteed inconspicuous? Or did you have Firebud make you over, so that you had no style at all?”

He gazes at her steadily, the same calm gaze. She can’t seem to touch it, or him. “I can’t say,” he says.

“How long have you worked for them?” she asks. “You were a mudboy once— you don’t have the look that they do. But you work for them now. Is that what they promised you? A new body when you get old? And if you die on one of these jobs here in the mud, a nice funeral with the corporate anthem sung over your body?”

“Something like that,” he agrees.

“Got you heart and soul, have they?” she asks.

“That’s how they want it.” Dryly, accepting. He knows the price of his ticket.

“Control,” she says. “You understand that. You are controlled by people who worship control, and so you control yourself well. But you’re a pressure cooker, and the steam is just under the surface. Do you go slumming in your off hours, like Princess? To the clubs, to the houses? Are you one of my old customers?” She gazes into his expressionless eyes. “You could be,” she says, “I never remembered faces.”

“As it happens, I’m not,” he says. “I never saw you before I was given this assignment.” He is beginning to look a little out of patience. Sarah grins.

“Don’t worry,” she says, and throws the holo of Princess on the table. “I’ll do your owners proud.”

“I’m sure you will,” he says. “They won’t have it any other way.”

IN THE ZONE/YES

Like Times Square neon the amber LED tracks across the upper limits of Sarah’s vision, just where the shadow of her brows would be.

PRINCESS MOVING PRINCESS MOVING PRINCESS MOVING . . .

The Aujourd’Oui is Princess’s favorite spot, but there are others. Sarah should be ready to move at need.

The washroom at the Aujourd’Oui is a conglomeration of mirrors and soft white lights, red flock on the gold wallpaper, bronze water spouts above the sinks, chromed dispensers offering tissue for the adjustment of makeup. Sarah shoulders through the door and a pair of dirtgirls standing in front of the mirrors glance at her. There is envy in their glance, and a kind of desperate awe, and then the eyes turn self-consciously back to the mirrors. The satin jacket represents something they want and will most likely never have, the freedom of the white crane to climb into the sky amid the silver glitter of stars. Sarah is suddenly aware of the sound of sobbing, magnified by the low ceiling, the hard edges of the room. The dirtgirls’ eyes stay fixed in their own reflections as she passes and steps into a stall.

It is the girl in the next stall who is weeping, pausing only to draw massive shuddering breaths before bringing the air out again past the tortured muscles of the throat. It hurts to cry that hard, Sarah knows. The ribs feels as if they are breaking. The stall shudders to the impact as the other girl, apparently, drives her head against its wall, and Sarah knows that it is pain the girl is seeking, perhaps to drive out pain of another kind.

Sarah tries not to get between people and what they need.

To the sound of the impacts Sarah takes her inhaler from her belt, puts it to her nose, and triggers it. There is a brief hiss of compressed gas. Sarah throws her head back, feeling the rush of the drug. The stall quakes. Sarah inhales again, using the other nostril, and she feels her nerves go warm and then cold, the hair on her forearms prickling. Her lips peel back from her teeth, and she feels at once abnormally sensitive and abnormally hard, as if her skin is made of razor blades that can feel every mote of dust. She needed the bite of the drug, needed it to give herself that extra piece of conviction. She hadn’t mentioned it to Cunningham— the hell with him— she would play it her own way . . .

PRINCESS MOVING PRINCESS MOVING. . .

The other girl’s weeping is a whining, grating sound, like a saw on bone, syncopated with hysterical crashing as she smashes again and again into the divider. Sarah can see flecks of blood daubing the floor of the next stall. She opens her door and sweeps through the room, past the dirtgirls whose eyes stand out pale amid their rimming of kohl as they gaze at each other and wonder what to do about the sobbing casualty. PRINCESS AUJOURDOUI REPEAT OUJOURDOUI AM SWITCHING POLICE TRANSMISSIONS GOOD HUNTING CUNNINGHAM.

Sarah blinks as she stepped into the darkness of the club, feeling the drug impelling her limbs to motion, and she rides the drug like a jock on the flaming roman candle of a booster, climbing for the edge of the sky and still in control. The corners of the room, the dancers and fixtures, flare like liquid- crystal kaleidescopes.

And then Princess comes, and Sarah’s motion freezes. Princess is surrounded by dirtboy muscle but she stands out clearly in the dark— there is an aura about her, a glow. She has the Look as none of them have, a soft radiance that speaks of luxury, soft and carefree joys, freedom even from gravity. A life even the jocks can’t share. It seems as if there is a pause in the music, as the room inhales in mutual awe. Two hundred eyes can see the glow and a hundred mouths, hungry for it, begin to salivate. Sarah feels her body tingle, flares of nerve-warmth at her fingertips. She is ready.

Sarah gives a soft private laugh, as if her triumph were already a fact, and walks long-legged across the darkened bar as Firebud has taught her, swinging her broad shoulders in counterpoint to her hips, insinuant animal style. She gives a grin to the muscle and holds her hands palms-out to show them she carries no weapons, and then Princess stands before her.

She is a good four inches shorter and Sarah looks down at her, hands cocked on her hips, challenging. Princess’ soft blonde hair is worn long, ringlets playing with her cheeks, her shoulders. Her eyes are circled with vast blooms of purple and yellow makeup, to look like bruises, making public the secret wish of a translucent white face that has never known pain. Her mouth is a deep violet, another laceration. She is wearing a creamy something that matches her blue, innocent eyes. Sarah cocks her head back and laughs low, baring her teeth, and thinks of the sounds hyenas make on the hunt.

“Dance with me, Princess,” she says to the wide cornflower of her eyes. “I am your wildest dreams.”

PRACTICE CREATES PERFECTION

PERFECTION CREATES POWER

POWER CONQUERS LAW

LAW CREATES HEAVEN

a helpful reminder from Toshiba

Nicole has a cigaret in the corner of her mouth and wears a jacket of cracked brown leather. She has dark blonde hair that reaches down her back in tawny strands, and long deep-grey eyes that look up at Sarah without a flicker.

“You can’t hesitate for a second, Sarah,” Cunningham says. “Not even the fragment of a second. Princess will know it and know there’s something wrong. Nicole is here for that. You are to practice with her.”

Sarah looks at Nicole for a moment of surprise and then barks a laugh. Anger bubbles in her whitely, coolly, like flares on the night horizon. “I suppose you plan to watch, Cunningham,” she says.

He nods. “Yes,” he says. “I and Firebud. You seemed uncertain at first about making love to a woman.” Nicole draws slowly on her cigaret and says nothing.

“Make a vid record, perhaps?” Sarah asks. “Give me post-game critique?” She curls her lip. “Is that your particular pleasure, Cunningham?” she demands. “Does watching this kind of vid keep your demons away?”

“We’ll destroy the vids together, if you like. Afterward.” Cunningham says.

Sarah has been two months in the training, has had her body altered and surgical work done, and all along she has been their willing dirtgirl. But however many candidates had been in Cunningham’s files she is sure she’s the only hope now, the only charge Cunningham will have shaped by the time Princess next comes down from orbit, and because she is the only one she knows she has power of her own. They will have to go with her or the project will fail, and it is time they knew it.

She shakes her head slowly. “I don’t think so, Cunningham,” she says. “I’ll be ready on the night, but I’m not now and I’m not going to be. Not for you, not for your cameras.”

Cunningham does not reply. He seems to squint a little, as if suddenly the light is stronger. Nicole watches Sarah with smoky eyes, then shakes her long hair and speaks.

“Just dance with me, then.” Her words come a little too abruptly, as if impelled by some form of desperation, and Sarah wonders what she has been promised, how she has been made vulnerable to them . When she speaks her voice gives her away; it is so much younger than her pose. “Just dance a little,” she says. “It’ll be all right.”

Sarah turns her gaze from Cunningham to Nicole and back, then nods. “Will a few dances satisfy you, Cunningham?” she asks. “Or do we end the program where we stand?”

His jaw muscles tighten, and for a moment Sarah thinks the business is done, that it’s over. Then he nods, still facing her.

“Yes,” he says. “If it has to be that way.”

“That’s how it has to be,” she says.t There is a moment of silence, then Cunningham nods again, as if to himself, and turns away. Nicole gives a nervous smile, wanting to please, not knowing who is her ticket to whatever it is she needs. Cunningham walks to the sound deck and presses a switch. Music buffets the walls. He turns back and folds his arms, waiting.

Nicole closes her eyes and shrugs out of her jacket. Either they have gone out of their way to find a woman of Princess’s build or they have been lucky. Sarah watches as Nicole sways her body to the music, the Plastic Girl, waiting blind to take an impression.

She steps forward and takes the girl’s hands in her own.

DELTA THREE EMERGENCY ATTEMPTED SUICIDE AUJOURD’OUI EMERGENCY

Deep in her zone, Sarah shakes her head to clear the sweat from her eyes and feels the drug biting her veins. Princess has been her partner all night. She leaps and spins and Princess watches with gleaming eyes, admiring. She feels like the crane on her back, arms stretching out to fly on pinions of purest silver. Sarah changes zones and Princess follows, letting her give a name to their motion, their liquid pattern. She is bringing Princess in closer until, like a wave, she can fall upon her from her crest of foaming white.

There is an intrusion into the zone, an attempted alteration in the pattern. Sarah whirls, an elbow digging deep into ribs, the zoneboy doubling with the impact. She slices at his neck with the sword hand and the boy flies from the zone whimpering. Princess is watching, rapt with glowing admiration. Sarah steps to her and catches her about the waist, and they spin like skaters on the edge of sharpened blades.

“Am I the danger that you want?” she asks. The blue eyes give an answer. I know you, old man, Sarah thinks in triumph, and bends her head to devour the violet lips, feasting like a raptor on her prey. The eyes of Princess widen, held in Sarah’s gaze. Her lips taste of salt, and blood.

TAMPA’S TOTALS OVERNITE, AS OF 8 THIS MORNING, 12 FOUND DEAD—

LUCKY WINNERS COLLECT AT ODDS OF FIVE TO THREE

Cunningham’s car hisses through the night on speed-blurred wheels. Holograms slide past the windows in neon array. Sarah watches the back of the driver’s neck as it swells from its collar. “It’ll be best if you go alone to the club,” Cunningham says. “Princess may send some of her people ahead, and you don’t want to be seen with anyone.”

Sarah nods. He’s given these instructions before and she can recite them word for word, even do a fair imitation of the whispery monotone. She nods to show she’s listening. Earlier this afternoon she’d collected the second payment of chloramphenildorphin and her mind was occupied chiefly with ways of putting it on the street.

“Sarah,” he says, and reaches into a pocket. “I want you to have this. Just in case.” His hand comes up with a small aerosol bottle.

“Yes?” she asks. She sprays it on the back of her hand, touches it, sniffs.

“Silicon lubricant,” he says. “The scent is right, and should last for hours. Use it in the washroom if you find that you aren’t really . . . attracted to her.”

Sarah caps the bottle and holds it out to him. “I don’t plan for it to go that far,” she says.

He shakes his head. “Just in case,” he says. “We don’t know about what happens when you go behind her walls.”

She shrugs and puts it in her belt pouch. She rests her reshaped jaw on her hand and stares out the window, the hologram adverts reflecting in her dark eyes, until the car slides to a stop at the door of her apartment.

She reaches for the latch and opens it, steps out. The heat of the outside comes in like a smothering blanket, and she can feel the sweat springing up on her forehead. Cunningham sits huddled in his seat, somehow smaller than he had been. Up until now, until the firing of his shaped charge, he’d been in control— but now he’d committed her to action and all he was able to do is watch the result and hope he’d calculated the ballistics correctly. His jaw muscles twitch in a tight smile and he raises a hand.

“Thanks,” she says, knowing he’s wished her luck without actually risking a curse by saying it, and she turns away and breathes out and feels a lightness in her body and heart, as if the gravity was somehow lessened. All she has left is the job. No more pleasing Cunningham, no more rules or training, no more listening to Firebud criticizing the very way she walks, the way she holds her head. All that is behind.

The apartment is splashed with video color and she knows Daud is home. He’s cleared the coffee table from the center of the room and is doing his exercises, the freeweights in his hands, the burning holograms outlining his naked body, his hairless genitals. She kisses his cheek.

“Dinner?” she asks.

“I’m going with Jackstraw. He wants me to meet someone.”

“Someone new?”

“Yes. It’s a lot of money.” He drops the weights and lowers himself to the floor, begins strapping another set of weights to his ankles. She stands over him with a frown.

“How much?” she asks.

He gives her a quick glance, green laserfire winking from his eyewhites, then he looks down. His voice is directed to the floor. “Eight thousand,” he says.

“That’s a lot,” she says.

He nods and stretches his back on the ground, raising his legs against the strain of the weights. He points his toes and she can see the muscles taut on the tops of his thighs. She slips out of her shoes and flexes her toes in the carpet.

“What does he want for it?” she asks. Daud shrugs. Sarah crouches and looks down at him. She feels a tightness in her throat.

She repeats her question.

“Jackstraw will be in the next room,” he says. “If anything goes wrong he’ll know.”

“He’s a thatch, isn’t he?”

She can see the adam’s apple bob as Daud swallows. He nods silently. She takes a breath and watches him strain against the weights. Then he sits up. His eyes are cold.

“You don’t have to do this,” she says.

“It’s a lot of money,” he repeats.

“Tomorrow my job will be over,” she says. “It’ll pay enough for a long time, almost enough for a pair of tickets out.”

He shakes his head, then springs to his feet and turns his back. He walks toward the shower. “I don’t want your money,” he says. “Your tickets, either.”

“Daud,” she says. He whirls around and she can see his anger.

“Your job!” he spits. “You think I don’t know what it is you do?”

She rises from her crouch, and for a moment she can see fear in her eyes. Fear of her? A wedge of doubt enters her mind.

“You know what I do, yes,” she says. “You also know why.”

“Because some man went thatch once,” he says. “And because when you got loose you killed him and liked it. I know the stories on the street.”

She feels a constriction in her chest. She shakes her head slowly. “No,” she says. “It’s for us, Daud. To get us out, into the orbitals.” She comes up to him to touch him, and he flinches. She drops her hand. “Where it’s clean , Daud,” she says. “Where we’re not in the street, because there isn’t a street.”

Daud gives a contemptuous laugh. “There isn’t a street there?” he asks. “So what will we do, Sarah? Punch code in some little office?” He shakes his head. “No, Sarah,” he says. “We’d do what we’ve always done. But it will be for them, not for us.”

“No,” she says. “It’ll be different. Something we haven’t known. Something finer.”

“You should see your eyes when you say that,” Daud says. “Like you’ve just taken uno pinchazo. Like that kind of hope is your drug, and you’re hooked on it.” He looks at her soberly, all his anger gone. “No, Sarah,” he says. “I know what I am, and what you are. I don’t want your hope, or your tickets. Especially not tickets with blood on them.” He turns away again, and her answer comes quick and angry, striking for his weakness, for the heart. Like a weasel.

“You don’t mind stealing my bloody endorphins, I’ve noticed,” she says. His back stiffens for a moment, then he walks on. Heat stings Sarah’s eyes. She blinks back her tears. “Daud,” she says. “Don’t go with a thatch. Please.”

He pauses at the door, hand on the jamb. “What’s the difference?” he asks. “Going with a thatch, or living with you?”

The door closes and Sarah can only stand and fight a helpless war with her anger and tears. She spins and stalks into her room. Her hardwired nerves are crackling, the adrenaline triggering her reflexes, and she only stops herself from trying to drive a fist through the wall. She can taste death on her tongue, and wants to run the Weasel as fast as she can.

The holograph of Princess sits on her chest of drawers. She takes it and stares at it, seeing the creamy shoulders, the blue innocence in the eyes, the innocence as false as Daud’s.

TOMORROW/NO

Sarah and Princess follow the ambulance men out of the Aujourd’Oui. They are carrying the girl from the washroom stall. She has clawed her cheeks and breasts with her fingernails. Her face is a swollen cloud of bruises, her nose blue pulp, her lips split and bloody. She is still trying to weep, but lacks the strength.

Sarah can see Princess’s excitement glittering in her eyes. This is the touch of the world she craves, warm and sweaty and real, flavored with the very soil of old Earth. Princess stands on the hot sidewalk while her dirtboys circle and call for the cars. Sarah puts her arm around her and whispers in her ear, telling her what Sarah knows she wants. “I am your dream,” Sarah says.

“My name is Danica,” Princess says.

In the back of the car there is a smell of sweat and expensive scent. Sarah begins to devour Danica, licking and biting and breathing her in. She left the silicon spray at home but won’t be needing it: Danica has Daud’s eyes and hair and smooth flesh, and Sarah finds herself wanting to touch her, to make a feast of her.

The car passes smoothly through gates of hardened alloy, and they are in the nest. None of Cunningham’s people ever got this far. Danica takes Sarah’s hand and leads her in. A security man insists on a check: Sarah looks down at him with a contemptuous stare and spreads the wings of her jacket, letting his electronic marvel scout her body. She knows Weasel is undetectible by these means. The boy confiscates her inhaler. Fine: it is made so as not to acquire fingerprints. “What are these?” he asks, holding up the hard black cubes of liquid crystal, ready for insertion into a comp deck.

“Music,” she says. He shrugs and gives them back. Princess takes her hand again and leads her up a long stair.

Her room is soft and azure, like the sky. Danica laughs and lies back on sheets that match her eyes, arms outstretched. Sarah bends over her and laps at her palate. Danica moans softly, approval. She is an old man and a powerful one, and Sarah knows his game. His job is to rape Earth, to be as strong as spaceborne alloy, and it is weakness that is his forbidden thing, his pornography. To put his bright new body into the hands of a slave is a weakness he wants more than life itself.

“My dream,” Danica whispers. Her fingers trace the scars on Sarah’s cheek, her chin.

Sarah takes a deep breath. Her tongue retracts into its Weasel’s implastic housing, and the cybersnake’s head closes over it. She rolls Danica entirely under her, holding her wrists, molding herself to the old man’s new girl-body. She presses her mouth to Danica’s, feeling the flutter of the girl’s tongue, and then Weasel strikes, uncoiling itself from its hiding place in Sarah’s throat and chest. Sarah holds her breath as her elastic artificial trachea constricts. Danica’s eyes open wide as she feels the touch of Weasel in her mouth, the temperature of Sarah’s body but still somehow cold and brittle. Sarah’s fingers clamp on her wrists, and Princess gives a birth-strangled cry as Weasel’s head forces its way down her throat. Her body bucks once, again. Her breath is hot and desperate in Sarah’s face. Weasel keeps uncoiling, following its program, sliding down into the stomach, its sensors questing for life. Daud’s eyes make desperate promises. Princess moans in fear, using his strength against Sarah’s weight, trying to throw her off. Sarah holds him crucified. Weasel, turning back on itself as it enters her stomach, tears its way out, seeks the cava inferior and shreds it. Danica makes bubbling sounds, and though she knows it is impossible, although she knows her tongue is still retracted deep into Weasel’s base, Sarah thinks she can taste blood. Weasel follows the vein to Danica’s heart. Sarah holds her down, her own chest near bursting with lack of air, until the struggling stops and Daud’s blue eyes grow cloudy and die.

Purple and black rim Sarah’s vision. She heaves herself off the bed, retracting Weasel partway as she gasps for air through the constricted passage in her throat. She stumbles for the washroom, falls and crashes into the sink. The impact drives the air from her. Her hands turn the spigots. Blind, her hands put the Weasel in the sink and feel the water running chill. Her breath comes in rasps. Weasel is coated with a gel that supposedly prevents blood and matter from adhering but she doesn’t want even a chance of Danica’s flesh in her mouth. The cybersnake is tearing at her breast. The water thunders until she can feel nothing but the speed with which she is falling into blackness, and then she falls back and sucks Weasel into her and can breathe again and taste the cool and healing air.

Her chest heaves up and down and her eyes are still full of darkness. She knows Daud is dead and that she has a task. She whips her head back and forth and tries to clear it, tries to scrabble upward from the brink, but Weasel is eating her heart and she can scarcely think from the pain. Sarah can hear herself whimper. She can feel the prickle of the carpet against the back of her neck as she raises her arms above her head and tries to drag herself along, crawling away, crawling, while Weasel throbs like thunder in her chest and she thinks she can hear her heart crack.

Sarah comes to herself slowly, and the black circle fades from her sight. She is lying on her back and the water is still roaring in the sink. She sits up and clutches at her throat. Weasel, having fed, is at rest. She crawls back to the sink and turns the spigots off. Grasping them, she hauls herself to her feet. She still has work to do.

In her room, Princess is still spread-eagled on the bed. Dead, it is easier to see the old man in her. There is a certain smell in the room, and Sarah realizes that Danica has emptied her bowels at the last minute. Her stomach turns over. She should drag Princess across the bed and tuck her under the covers, delaying the moment when they would find her, but she can’t bring herself to touch the cooling flesh; and instead she turns her eyes away and steps into the next room of the two-room suite.

She pauses as her eyes adjust to the dim light, and listens to the house. Silence. She reads the amber Times Square lights above her vision and can find only routine broadcasts. Sarah takes a pair of gloves from her belt pouch and walks to the room’s comp deck. She flicks it on, then opens the trapdoor and takes from her pouch one of the liquid-crystal music cubes Cunningham has given her. She puts it in the trapdoor and waits for the deck to signal her.

The cube would, in fact, have played music had anyone else used it. Sarah has the code to convert it to something else. The READY signal appears.

She taps the keys in near-silence as she enters the codes. A pale light flashes in the corner of the screen: RUNNING . She leans back in her chair and sighs.

Princess was a courier, bringing complex instructions down from orbit, instructions her company dared not trust even to coded radio transmissions. Princess would not have known what she carried; it would only have been on a crystal cube she was guarding. Sarah herself has no clear idea, though presumably it contained inventory data, strategies for manipulating the market, instructions to subordinates, buying and selling strategies. Information worth millions to any competitor. The crystals cube would have been altered to a new configuration once the information was removed to the company computer— a computer sealed against any outside tampering, but which could presumably be accessed through the terminals in the corporate suites.

Sarah also has no clear idea what is on the cube she is carrying. Some kind of powerful theft-program, she presumes, to break its way through the barriers surrounding the information so that it can be copied. She does not know how good her program is, whether it is setting off every alarm in Florida or whether it’s accomplishing its business by stealth. If it’s very good it will not only copy the information, but alter it as well, planting a flow of disinformation at the heart of the enemy code, perhaps even altering the instructions as well, sabotaging the enemy’s marketing patterns.

While the RUNNING light blinks Sarah stands and goes over every part of the suite she might have touched, stroking anything that could retain a print with her gloved fingertips. The house, and Princess, are silent.

It is eleven minutes before the computer signals READY . Sarah extracts the cube and returns it to her belt. She has been told to wait a few hours, but there is someone dead in the next room and every nerve screams at her to run. She sits before the comp deck and puts her head between her legs, gulping air. For some reason she finds herself trembling. She battles the adrenaline and her own nerves, and thinks of the tickets, the cool dark of space with the blue limb of Earth far below, forever out of reach.

In two hours she calls herself a cab and walks down the cold, echoing stair. The security man nods at her as she walks out: his job is to keep people from coming in, not to hinder their leaving. He even gives her the inhaler back.

She takes a dozen cabs to a dozen different places, leaving the satin jacket in one, cinching her waist in tighter and removing the suspenders in another, in a third reversing her tee shirt and her belt pouch, both now glowing yellow like a warning light. The jock persona is gone, and she is dirt again. She finishes her journey at the Plastic Girl, the place still running flat-out at four in the morning. As she walks through the sounds of dirt life assault her, and she takes comfort. This is her world again, and she knows all the warm places where she can hide.

She takes a room in the back and calls Cunningham. “Come and get your cube,” she says, and then orders rum and lime.

By the time he arrives she’s rented an analyzer and some muscle. He comes in alone, a package in his hand. He closes the door behind him.

“Princess?” he asks.

“Dead.” Cunningham nods. The cube is on the table before her. She holds out a hand. “Let’s see what you’ve got,” she says.

She checks three vials at random and the analyzer tells her it’s chloramphenildorphin, purity 98% or better. She smiles. “Take your cube,” she says, but he plugs it into the room’s deck first, making sure it has what he wants. Then he puts it in his pocket and heads for the door.

“If you have another job,” she says, “you know where to find me.”

He pauses, a hand on the knob. His eyes flicker. She receives an impression of sadness from him, as if he were mourning something newly dead.

He is an earthly extension, Sarah knew, of an Orbital bloc. She doesn’t even know which one. He is a willing tool and an obedient one, and she has fed him her scorn on that account, but that doesn’t disguise what they both knew. That she would give all the contents of the packet, and everything else besides, if she could have his ticket, and on the same terms. “I’ll be on the ramp in an hour,” he says. “Going back to orbit.”

She gives him a grin. “Maybe I’ll be seeing you there,” she says.

He nods, his eyes on hers. He starts to say something, then turns himself off again, as if he realizes it’s pointless. “Be careful,” he says, and leaves without another glance. One of her hired muscle looks in at her.

“It’s clear,” she says. The muscle nods.

She looks at the fortune in her hand and feels suddenly hollow. There is a vacuum in her chest where the joy should be. The drink she has ordered tastes as flat as barley water, and a headache throbs in time to the LED light burning in her forehead. She pays off her hired muscle and takes a cab to an all-night bank, where she deposits the endorphin in a rented box. Then she takes the cab home.

The apartment hums softly, emptily. She finds the control to her LED and turns it off, then throws her clothing in the trash. Naked, she steps into her room and sees the holo of Princess on her night table. Hesitantly, she reaches out to it, then turns it face down and falls into the welcoming blackness.

LOVELY AND WAITING FOR YOU

TERRY’S TOUGH ‘N’ TENDER

NOW

It is still night when she awakens to the sound of the door. “Daud?” she asks, and is answered by a groan.

He is wrapped in a sheet and covered with blood. Jackstraw holds him up, panting, his neck muscles straining. “Bastard,” he says.

She picks Daud up like a child and carries him to her bed. His blood smears her arms, her breasts. “Bastard went thatch,” Jackstraw says. “I was only gone a minute.”

Sarah arranges Daud on the bed and unwraps the sheet. A whimpering sound forces its way up her throat. She puts her hand to her mouth. Daud is striped in blood, the thatch must have used some kind of weighted whip. Weakly, he tries to move, raises a hand as if to ward a blow.

“Lie back,” Sarah says. “You’re at home.”

Daud’s face crinkles in pain. “Sarah,” he says, and begins to cry.

Sarah feels tears stinging her own eyes and blinks them away. She looks up at Jackstraw. “Did you give him a pinchazo?” she asks.

“Yeah. First thing.”

“How much?”

He looks at her blankly. “Lots. I don’t know.”

“You weren’t supposed to leave the next room,” she says.

His eyes slide away. “It was a busy night,” he says. “I was only gone a minute.”

She turns her eyes back to Daud. “It took more than a minute for this,” she says. “Get the fuck out.”

“It’s not— ”

There is a savage light in her eyes. She wants to tear him but she has other things to do. “Get the fuck out,” she repeats. He hesitates for another instant, then turns away.

She cleans the cuts and disinfects them. Daud cries silently, his throat working. Sarah looks for his injector and finds it, loads it with endorphins from his cache, and guesses at a dosage. She puts it in his arm, and he says her name and goes to sleep. She watches for a while, making sure he hasn’t taken too much, and then puts the covers over him and turns down the light. “Just lie back,” she says. “I’ve got the price of your ticket.” She leans down to kiss his beardless cheek. The bloody sheet goes in the trash.

Daud normally sleeps on the convertible sofa in the front room, and after making sure he is asleep she moves to the other room and, without bothering to open the sofa, lies down on it. The room hums, and for a long while she listens. She doesn’t have the strength to sleep.

LIVING IN THE DEAD ZONE?

WE GUARANTEE A PAYOFF

The explosion has enough force to throw the sofa against the far wall. Sarah feels hot rush of wind that tears the breath from her throat, the elevator-sensation of the world falling away, and then a final impact as the wall comes up. Screams are ricocheting from every corner, all the screams that Princess never uttered. There are fires licking like red laserlight and the sounds of nightmares.

She heaves herself to her feet and runs for the other room. She can see by the light of the burning bed. Daud is sprawled in a corner of the room, and parts of his body are open and other parts are on the walls. She is screaming for help, but alone she manages to get the burning bedding out of the apartment, through the hole in the wall. Outside, the hot tongues of morning are rising in the east. She thinks she can hear Daud call her name.

BODY NEEDING WORK?

WE DELIVER

The ambulance driver wants payment in advance, and she opens her portfolio by comp and transfers the stock without questioning the prices he gives her. Daud dies three times before the driver’s two assistants can get him out of the apartment, and each time they bring him back the prices go up. “You got the money, lady, and he’ll be fine,” the driver tells her. He looks at her nakedness with appreciative eyes. “All kinds of arrangements can be made,” he says.

Later, Sarah sits in the hospital room and watches the doctors work and is told their rates of payment. She will have to make plans to convert the endorphin quickly, within a few days. Machines attached to Daud hiss and thump. The police surround her and want to know why someone would fire a shaped charge at her apartment wall from the building across the street. She tells them she has no idea. They have a lot of questions but that seems to be the most frequent. Eventually she puts her head in her hands and shakes her head; and they shuffle for a while and then leave.

She wishes she had the inhaler: she needs the bite of the drug to keep herself alert, to keep her mind functioning. Thoughts hammer at her. If Cunningham’s people had been in her apartment they would have known that she had slept in the back room, Daud in the front. They waited till the lights went down and she had the time to get to sleep, then fired with a weapon that would smash through the wall and scatter burning steel through the inside. They hadn’t trusted that she wouldn’t tell someone or that she wouldn’t try to use the pieces of knowledge she had gained as leverage for some shifty little dirtscheme of her own.

“Who would I tell?” she wonders.

She remembers Cunningham at that last moment in the Plastic Girl, the sadness in him. He had known. Tried, in his way, to warn her. Perhaps the decision had not been his; perhaps it had been made over his objection. What did the orbitals care for one more dirtgirl, when they had already killed millions, and kept the rest alive only so long as they were useful currency?

The Hetman glides into the room on catlike feet. He wears a gold earring and his wise, liquid eyes are surrounded by the spiderwebs of the old hustler’s dirtbound life. “I am sorry, my sister,” he says. “I had no indication it would come to this. I want you to understand.”

Sarah nods numbly. “I know, Michael.”

“I have people on the West Coast,” the Hetman says. “They will give you work there, until Cunningham and his people forget you exist.”

Sarah looks up at him for a moment, then looks at the bed and the humming, hissing machines. She shakes her head. “I can’t go, Michael,” she says.

“A bad mistake, Sarah.” Gently. “They will try again.”

Sarah makes no reply, feeling only the emptiness inside her, knowing the emptiness would never leave if she deserted Daud again. The Hetman stands for an uncomfortable moment, and is gone.

“I had the ticket,” Sarah whispers.

Outside she can see the mud boiling under the lunatic sun. All Earth’s soil, looking for their tickets, plugging into whatever would give them a fragment of their dream. All playing by someone else’s rules. Sarah has her ticket, but the rules have turned on her like a weasel and she must shred the ticket and spread it on the street, spread it so she can watch the machines hum and hiss and keep what she loves alive. Because there is no choice, and all the girls have no option but to follow the instructions, and play as best they can.