Totality in Curacao

What follows dates from February 1998, when we visited the island of Curaçao for what had to be one of the most glorious coincidences of all time— a total eclipse of the sun occurring within a few days of Mardi Gras. Naturally I managed to get in some fine eating, diving, and drinking as well. Enjoy.

What follows dates from February 1998, when we visited the island of Curaçao for what had to be one of the most glorious coincidences of all time— a total eclipse of the sun occurring within a few days of Mardi Gras. Naturally I managed to get in some fine eating, diving, and drinking as well. Enjoy.

(Text and images copyright 1998 by Walter Jon Williams, and may not be reproduced without permission.)

2/22/98

“I think you would see a lot of really drunk people.”

You probably don’t want to hear about the two-day trip to Curaçao, crammed into very narrow American Airlines seats, the overnight stay in Miami (the Comfort Inn was a dive, in its modest way), Kathy and I sweltering under the burden of too much baggage (ten days’ clothing, cameras, a laptop computer, a

big bag of dive gear, a large and implastic telescope).

By the time we got to the Princess Beach Hotel and Casino, the all day Carnival parade scheduled to march for six hours that Sunday was over. We could have gone down to the football stadium, where the parade ended, and danced with mobs of really drunk people, but we were too tired, and probably not drunk enough. (The paraders march marched next to carts equipped with three-foot-high bottles of Scotch, which they swilled like Kool-Aid in the tropical heat.)

The Princess Beach Hotel was geared to very rich American tourists. This is the place to go if you want to drink four-dollar beers or six-dollar cocktails (plus tax, plus automatic 10% service charge). The casino does its business in dollars. We ate a dinner which was gastronomically merely okay, but which set us back surprising amounts of money.

And who are “we,” you ask? I, Walter Jon Williams, your host. Kathy Hedges, my spouse and astronomical advisor. And our two friends Eileen Comstock, an M.D. from Socorro, NM, and her husband Warren Marts, computer guy, sometime geologist, and former Microserf (“I got to the point where I had lunch with Bill Gates, and then I quit.”). As the result of a spinal injury sustained when he fell off a mountain in Oregon five years ago, Warren spends most of his time in a wheelchair, though he can also get by with crutches, a brace on his useless left leg, and large amounts of true grit.

Curaçao is part of the Netherlands Antilles, otherwise known as the ABC Islands, for Aruba, Bonaire, and Curaçao. It is no longer a colony, and since the 1950s has been administratively part of the Netherlands, though it has a local Parliament, the chief function of which (according to some of the complaints I heard) is to raise taxes enough to destroy local business, wreck the economy, and keep the population dependent on government handouts.

(Colonialism by other means, perhaps.)

The island’s first known inhabitants were the peaceful Arawak Indians, who did not long survive the island’s first contact with Columbus, in 1499. In 1505 Spanish slavers rounded up most of the island’s able-bodied Arawaks and shipped them to Haiti to work in the silver mines. Curaçao has an arid, desertlike climate, and the local flora include a lot of scrub and a truly astounding array of cactus. Because the climate was unsuitable for plantation agriculture, the Spanish categorized the island as inutiles (useless) and largely left it alone. Some large-scale ranching was done in the 16th century

by Juan de Ampues, who brought in cattle, goats, sheep, horses, and 200 slaves. An attempt to start a plantation of Valencia oranges failed when the oranges turned out wrinkled, withered, and largely moisture-free, but the highly concentrated flavor later turned out perfect for making Curaçao liqueur.

In 1634 the Dutch West India Company conquered the place and founded the city of Willemstad on a large natural harbor. The Dutch knew the island was unsuitable for plantations– though this did not stop them from founding a lot of them — but wanted it for the easily fortified natural harbor and for the general purpose of boosting their trade throughout the Caribbean.

One of the first governors was none other than Peter Stuyvesant, the one-legged character who was also governor of New Amsterdam.

One of the island’s unique characteristics was the large settlement of Sephardic Jews, settled by the Dutch beginning in 1651. The Sephardim, expelled from Spain, were believed capable of trading with the Spanish. They flourished on the island, at one point owning over 1200 ships and providing the island with 200 sea captains. Temple Mikve’ Israel, consecrated in 1732, is the oldest synagogue in the Western Hemisphere.

Despite the absence of large plantations, the island’s economy was still based on slavery. Curaçao was the transshipment point for tens of thousands of slaves. Dutch ships would bring slaves to the island, where they would be

housed in barracks, rested, and fattened up after the rigors of the Middle Passage, after which the slaves would be shipped off to markets throughout the New World. And, as in some Louis Farrakhan hate fantasy, the Sephardim

flourished along with slavery.

The island’s economy collapsed with the end of slavery in the 1860s, and the island began exporting laborers to the cane fields of Cuba. The economy picked up a bit in the 1920s when Royal Dutch Shell built a refinery in

Willemstad, but the refinery was closed in the 1970s and the economy nose-dived again. Throughout the 80s, the island tried to develop tourism. The refinery was eventually reopened, but as of 1998 the unemployment rate is 30%,

the crime rate is skyrocketing, and drugs are everywhere.

The island’s population visibly reflects its eclectic Indian/Spanish/Sephardic/ Dutch/African roots. The local language is a Creole called “Papiemento,” which is spoken very quickly and sounds like one of those polysyllabic languages that natives speak in those Bwana Sahib movies of the 1930s (and which, when translated, proves to say things like “I believe Johnny Weismuller has a small penis”). Most of the words in Papiemento are Spanish– Venezuela is just over the horizon– but they are spoken with African inflections, alongside lots of loan words from other languages, and nothing in the way of formal grammar. Sample phrases include “Bon Bini” (welcome), “Kon ta bai?” (How do you do?), “Mi ta bon, danki,” (Fine, thanks), and “Pasa un bon dia!” (have a nice day)

In school the children learn Papiemento, Dutch, English, and Spanish. Dutch children, who might return to the Netherlands, are given the option of learning German instead of Spanish.

After dinner, we took a swim in the pool, gazed at the ocean and palm trees, had some six-dollar cocktails, and generally kicked back.

Next day, we’d do some diving, and have our first encounter with Carnival 2/23/98

“Take us to the Parade!”

I went aboard the dive boat next morning to find Eileen and Warren already aboard. Warren was in his wheelchair, which had been strapped into the boat near the stern. (Despite his injury, Warren wanted to renew his scuba chops. Which is cool.)

Our divemistress was Vivienne, a Dutch woman who was, let’s face it, a babe. She was a student who worked as a divemistress to earn her way through college. She was a sight for my sore, jetlagged eyes, and flirted with me quite pleasantly on those occasions when we had a chance to chat.

We zoomed out through the breakwater and right into El Niño. Due to worldwide weird weather, the northeast trades hadn’t hit the island, and we were getting a stiff breeze from due south, which is unheard of. Big waves were slamming into what is normally the leeward side of the island. The boat jumped up and down, spray shooting everywhere. Warren got soaked in his wheelchair, and ended up crawling forward to shelter in the cabin.

Vivienne decided to abandon our primary dive site, and the secondary, too. The sea was just too rough. So we ended up in sheltered Directors Bay, so called because it was once the private beach of the directors of Royal Dutch Shell.

Warren and Eileen were diving together, so I got assigned a dive buddy, Jan the Yachtsman. He was another Dutch student with an unusual job, that of yacht skipper. He delivers yachts on behalf of the owners, and decided to

dive after finding out that in the next year he was to deliver yachts to two prime dive sites, Eilat and the Marquesas. Jan had only learned to dive a few months before, but he was very cool and competent, and a pleasure to dive

with.

The dive plan was simple. Go down with your buddy to 60-80 feet, swim against the current along the coral wall till you use half your air, rise to 30 feet, swim back. Once back in shallow water, we were to “look for squits,” as

Vivienne put it. This is pretty much the standard dive plan for Curaçao, one we were to follow for most of our dives. Usually without the squits, however.

While donning my gear, I managed to break no less than three things. My snorkel strap, the strap that holds my instrument console across my chest, and the zipper on my wet suit. So I dove the whole week just in my hot skins,

which don’t provide any thermal protection. Fortunately I am well insulated, and never really got chilled.

Having so much equipment fail at once is just one of those things you have to get used to as a diver.

Over the brink we went. The coral wall at Curaçao is not a vertical wall like Cozumel or the North Wall of Cayman (which drops 36,000 feet straight into the Cayman Trench). The wall drops more gradually, at maybe 60 or 70 degrees, with lots of broken-up coral blocks that made ideal moray country. The coral at Directors Bay was sort of beat up, though there was still plenty of it.

There were not a whole lot of fish to look at. We found a spotted moray at 85 feet, which was quite deep for a moray, and surprised us. At once point we found ourselves following a three-foot sea turtle which was cruising the reef

just below us. (I thought the turtle was quite clearly a hawksbill, but others insisted it was a green turtle.) Apparently the turtle wanted a look at us, too, because it swam up within about six inches of my face, then turned around and headed back in the direction from which we’d come.

Well, this was pretty marvelous. We’d pretty much reached our turn-around point, so we turned about and followed the turtle back to the rest of the divers, where he apparently decided the water was too crowded, so he headed

back to the Big Blue.

The next dive was at Caracas Bay, another sheltered area. There was a spit of coral that stuck out into the sea, and the idea was to head out along one side, and back along the other. We did this, and then, because we had air

left and nothing better to do, did it all again. Didn’t see much. Lots of large trumpetfish, which are long, skinny fish that do their best to imitate seaweed and generally swim head-downward. I pursued a porcupinefish in hopes of getting it to puff up into a spiky volleyball, but it eluded me.

After which lunch, then siesta.

We had choices after siesta. The Royal Astronomical Society of Canada (of Calgary), with which we had come, were going out to the eclipse observation site to check out the night stars. Or we could attend the Farewell to Youth

Carnival Parade.

Well. Guess which we decided to head for.

The parade was supposed to pass right by the hotel, so initially our plan was to sit in chairs on our hotel balcony and watch from there. But then we heard they’d moved the parade route, and everyone we talked to gave us a different

story, so finally we hailed a cab and said, “Take us to the parade!” The cab got us within a couple blocks, and from thence it was an easy enough walk.

The parade was half over by the time we got there. It was a children’s parade, with hundreds of kids in elaborate costumes, dressed as flowers, butterflies, celestial objects, etc. First would come a huge semitruck with a

40KV generator and a live band playing the tumba music of the island at ear-splitting volume. (Tumba is pronounced “tambu,” just to make it confusing for the tourists.) Following the semitruck came a sign explaining which outfit was sponsoring this segment of the parade, then lots of children in costumes, then a refreshment truck pouring drinks for the marchers, who by this point had been going for six hours. Then another truck, another parade, and more drinks.

After the parade ended, a whole mob of locals followed, dancing to the tumba.

We dispersed to dinner, at the Fisherman’s Wharf between the parade site and our hotel. Warren was quite nonchalant about the way he was taking his life in his hands zooming his wheelchair through the post-parade traffic, on narrow

streets full of construction, drunken drivers, and other hazards. (Not that he had a whole lot of choice, I guess.)

The meal turned out to be the best we had on the island. I opened with sopi piska, the local fish soup, tangy and choked with freshly-caught fish, squid, and lobster. I followed with grilled dradu (dorado, king dolphin, or mahi-mahi), with a sauce “in the style of the fisherman’s wife,” with tomatoes, onions, garlic, and ketjap. Kathy had a filet mignon stuffed with Dutch cheese. Top of the line stuff, by jove. The astronomers didn’t know what they were missing.

Then back through the darkness and traffic to the hotel for more overpriced drinks, then bed.

————

2/24/98

“Who Gonna Come Down an’ Dance?”

There was no diving on Fat Tuesday. We reserved the day for playing tourist

and going to the last big Carnival parade.

During the morning, till it got too hot to move, we wandered about Willemstad.The upscale portion of the town, Punda, is a strange mixture of the Dutch and the Tropical. The buildings tend to be tall and narrow, as in Amsterdam, and feature the traditional Dutch baroque gable-ends and other architectural features. (The penchant for lace curtains is another carryover from the Old Country.) But the buildings are painted in blazing tropical colors, in particular an avocado green and a distinctive shade of mustard yellow.

Turns out there’s a reason for this. One of the Dutch governors announced

that the color white, under the blazing tropical sun, gave him migraines, and

so passed an ordinance that buildings on Curaçao had to be a color other than

white. It was only years later that it was revealed that this particular

governor owned the paint factory in Holland that supplied the island.

We pause for a reverent moment to remember that the Dutch invented capitalism.

Willemstad features Queen Emma’s Bridge, a pontoon foot bridge built across the ship channel in the 19th century by the then-American consul. (We should remember that enterprising Yankees aren’t so bad at capitalism either.) When

a ship goes through, the entire bridge swings out to the shore of Otrabanda, which is the part of Willemstad on the far side of the channel. The bridge is a nice, effective bit of obsolescent technology, picturesque and obviously

much appreciated by the inhabitants.

Also in Willemstad is the Floating Market, where fishermen park their boats to sell their catch of the day, and where Venezuelans hawk vegetables from boats bobbing alongside the pier. These used to bring only a boatsworth of

vegetables at a time, then return home, but now they stay for months and are supplied by a weekly freighter, presumably at some cost in freshness and in the picturesque.

We also stopped by Temple Mikve’ Israel, the oldest synagogue in the Western Hemisphere, dated 1732. It’s a distinguished old building, very large, with huge brass chandeliers and candlesticks. The floor, strangely, is deep white

sand, which commemorates the days of the Spanish Inquisition, when Jews had to meet secretly in private homes, and covered the floor with sand so people wouldn’t hear them go in and out.

Luncheon was at the Grill King, in the old fort overlooking the sea, where I watched freighters go in and out and ate some splendid BBQ ribs in Chinese black bean sauce. Warren ordered some of the best shrimp I’ve ever tasted.

Done in garlic and butter, I think, with a touch of curry. I will have to make experiments in that direction.

We also got an early start on Carnival Fun by ordering Grill King Specials, a sinister blue concoction made of rum, blue Curaçao, pineapple juice, and other ingredients. Tasty, and about 100 proof.

After the heat of the day grew oppressive, we returned to the hotel for siesta, and to rest up for Carnival.

Carnival, we should remember, is Latin for “getting back to the flesh.” I planned to get back to the flesh in a big way.

About half the astronomers went out to the eclipse site to view the stars, but the rest of us piled into our trusty bus and roared through dense crowds to the parade site. We had bleacher seats reserved for us. On arrival, we were

handed tickets for food and drink and a cushion to sit on. Noting that I happened to have six drink tickets, I opted for a six-pack of Amstel, which I carried back to the bleachers with me. (I didn’t want to miss any of the parade just ‘cuz I was thirsty.) Dinner turned out to be grilled chicken in peanut sauce, a crab salad, slaw. Nothing to complain about there.

Our bleachers had a mistress of ceremonies, who did her damndest to pump up the crowd. It was a tough audience, as most of the group suffered from two serious disadvantages as far as Carnival fun was concerned.

1. They were scientists.

2. They were Canadian.

The national characteristics that built the best public health care system in the world are not necessarily the same traits that let one hang it all out on the Day of Getting Back to the Flesh. But the Canadians weren’t alone in this: even the locals in our bleachers were remarkably sedate. Maybe they were Carnival’d out.

Our poor hostess couldn’t get anyone (except, well, me) to stand up and dance, she had a hard time getting them even to wave their arms back and forth, and for the most part had to settle for polite applause. Eileen spent the entire

time with her head down and fingers jammed in her ears.

The parade consisted of the best bands and acts from all the previous Carnival parades over the last several months. (Carnival parades begin in June, believe it or not) By this point, the winning tumba song has been chosen in

the tumba contest, and all the bands had learned it. The semitrucks were back, with those 40KV generators pumping out the volume from eighteen-foot-high stacks of amps. Behind the semis came the paraders, in remarkably ornate

home-made costumes, of samba dancers, astronomical objects, butterflies, and even bats. (Curaçao features the world’s only fish-eating bats.) Behind the dancers came the trucks with drinks. One either goes with the flow or sticks

fingers in one’s ear. I was into that flow thang, myself.

So I danced and jumped around, and I suspect my Canadian neighbors thought I was nuts. One of the parade groups started dragging people out of the stands to dance in the street. They were highly reluctant. “Who gonna come down an’

dance?” our hostess wailed in despair.

So guess who bounded down out of the bleachers? The poor young thing who got me for a dance partner didn’t seem to know quite what to do with me, but I think we all managed to have fun. Even the Canadians seemed to think it was

time to holler.

After three hours the last of the paraders passed. The crowd danced after, on into town to help with the ritual burning of El Rei Momo, the Carnival King. We, ears ringing, had to climb back aboard our bus for the trip to the hotel.

At least we’d gotten back to the flesh.

————

2/25/98

“Oops– we’ve lost two divers.”

In 1977, the 230-foot-long cargo vessel SUPERIOR PRODUCER left Willemstad bound for the open sea. The ship was overloaded and began taking on water almost immediately. When the pumps jammed, the ship’s captain called for tugboats to come out and take him back to port. The tugboats scrambled and headed to the rescue.

During which time the captain repaired his pumps. You don’t have to pay a

tugboat unless it actually tugs you somewhere, so the captain called the tugs and told them to go home. Which they did. At which point the freighter’s pumps failed again.

The captain called for the tugboats, but this time they declined to respond, presumably filling the airwaves with salty Dutch imprecations. The captain turned SUPERIOR PRODUCER around and tried to get back to port on his own, but the harbor master was afraid the ship would sink in the channel and refused to open the bridge for him. SUPERIOR PRODUCER made a sharp 90- degree turn in order to avoid the harbor entrance, took on a lot more water, and sank. The crew all escaped in boats.

All of which is by way of explaining why there’s a big wreck lying on an even keel in 100 feet of water just northwest of Curaçao’s harbor, very close to

shore.

Wednesday morning, still feeling a bit buzzed from Carnival, we sallied forth to dive SUPERIOR PRODUCER. The winds had shifted to their more accustomed northeasterly position, but there was still a heavy chop on the water, and a wicked three- or four-knot current heading in the general direction of Cuba. The buoy that marked the wreck’s position had parted company from the wreck, so our divemaster Alan (the highly babacious Vivienne wasn’t along this time)

went over the side with an anchor line and tied it to the wreck. The plan was for us to climb down the mooring line so that the current wouldn’t sweep us

away.

I had Eileen as my dive buddy on this trip. Warren, who swims with his arms and a flipper on his one good leg, had decided to buddy with a divemaster on this trip, just in case he needed someone strong to haul him someplace.

The chop and the current had me thoroughly winded just getting to the anchor line. I hate going down when I’m out of breath and pissed off, but there wasn’t a lot of choice, so down we went, while the mooring line jerked around

and tried to fling us off. There was a lot of particulate matter in the water from the unprecedented wind of the last few days, so there was nothing to look at as we went down, until suddenly the bow of SUPERIOR PRODUCER loomed up out of the blue below us.

It wasn’t quite as impressive as the bow of TITANIC looming up in the James Cameron film, but it was on the same order. We dropped to the foredeck, where the ship’s crane lay where it had been since, as the best writers would

remark, “that fateful day in 1977.” The current was lessened close to the reef, so we we had no trouble floating up over the bows and then down through the open hatches into the cargo hold.

Everything movable on the ship had been either salvaged or stripped by divers, so the hold was empty. It was still rather impressive, a big ribbed empty space splotched by coral and sponges. We headed rearward to the

superstructure. The bridge was empty, with windows gaping to the void. Below the bridge was the captain’s cabin, with his table and shaving mirror still in place. The mirror was the only surface not crusted by marine life, and it was

eerie to find it there, still on the wall, like a mirror into another world.

On the floor of the captain’s cabin was the hatch to the engine room. It was full of silt, wire, cable, and machinery, and did not look inviting. We did not go further.

On our way back to the bow, Alan caught up with us and signalled us to ascend. We had reached our limit of 17 minutes. So back we went up via the mooring line, did our decompression safety stop at 15 feet, and back to the boat.

It was disappointing not to find any large blue diamonds or pictures of a naked Kate Winslet, but it wasn’t bad even so.

Our next dive was a drift dive at a place called Small Wall. In drift dives, the current works with you, so what we had was a nice relaxing dive, no exertion. The coral wall was lovely, though there didn’t seem to be much in the way of fauna. A large lobster, a small barracuda, a very big grouper.

When we got back on the boat and were ready to head to port, divemaster Johann did a head count and found that two of our group were missing. So he flung on his gear and plunged back into the briney. There was modest suspense for five minutes or so– we weren’t terribly worried, since the dive was so dead simple it was difficult to picture a pair of divers screwing up— and then the two missing folks showed up. They hadn’t been lost, they’d just been taking their time.

For dinner Warren wanted Indonesian, so we ate at the Rystaffel restaurant, where we had rijstaffel, which not surprisingly is the only dish, or rather dishes, they serve at the Rystaffel. I presume the difference in spelling is

accounted for by the various languages of the island. At least they didn’t spell it “smorgasbord.”

We had the medium-sized rijstaffel, which featured only 24 dishes. It wasn’t the best rijstaffel I’ve had, but some of it was very good, and none of it was awful.

After a dessert of ginger and coconut ice creams, we repaired to our rooms to digest for a while before doing a night dive. We had arranged with Peter Hughes Divers, our dive outfit, to have tanks and weights waiting for us on

their pier.

Warren was too tired to join me and Eileen after his earlier dives and the big meal, and therefore missed the best dive of our trip.

From the pier overlooking the sheltered waters inside the breakwater, we could see a dozen or so large squid– “large” in this case being a little over a foot long– hovering in the water off the pier. I was looking forward to swimming with what Vivienne would have called the “squits,” but as soon as we entered the water, the squids vamoosed. They are very fast when they want to be.

We swam on the surface to the entrance to the breakwater, then dropped to the bottom and followed the reef out to 50 feet. Turned right, floated along the reef. Once we got away from the lights of the pier, the water was utterly black, and the universe seemed narrowed to ourselves, weightless in the warm water, and the reach of our lights.

We found some lobsters, a very large green moray, a large red crab, and a large number of porcupine fish. I caught one of the porcupines, and it blew up in my hands to a prickly sphere the size of a volleyball. I handed it to Eileen, who had not encountered one of these animals before, and who thought it was some kind of plant form until she let it go and observed that it swam off.

Phosphorescence flew off our fins, and from our fingertips. The coral growths were brilliant colors in our lights. We got to the halfway point, rose to thirty feet, and returned.

I was very proud of my navigation– I managed to bring us back through the breakwater and to the foot of the pier. As we climbed out of our gear, I looked down at the water and noticed that the squids were hovering there again, watching us with their big plate eyes. A weird omen, but not a particularly ominous one.

Next day was the solar eclipse.

—-

2-26-98

“Oh my Gawwwwwwwwd . . . ”

The bus for the eclipse site left at 8:00am, even though the eclipse wouldn’t start until 12:42, and there wouldn’t be totality till 2:12.

You gotta give those astronomers time to set up their gear. And of course the early astronomer gets his choice of sites.

We were the first group on the site. And then, once Kathy set up her Astroscan, which took maybe ten seconds, we had nothing to do. For hours.

The government of Curaçao had assisted the cause of science by bulldozing flat about 20 acres near the island’s North Point. About 20 empty shipping containers had been piled up, two high, into a long wall to serve as a windbreak. Big concrete objects, the sort used to close off highways to traffic, had been scattered around to serve as bases for equipment. Tents had been set up as sun shelters, folding chairs and tables were provided, ambulances and a first aid tent stood ready, and local merchants were ready to provide food and drink. It was a first-class effort.

Next time there’s an eclipse, the government of Curaçao will know what to do. Unfortunately there won’t be another eclipse on Curaçao till the 27th Century.

Next time there’s an eclipse, the government of Curaçao will know what to do. Unfortunately there won’t be another eclipse on Curaçao till the 27th Century.

We sat around under canvas and read books and magazines and drank coke and beer. The astronomers stood in the strong sunlight on a flat hot surface and turned red as lobsters. Journalists wandered around looking for something to do. A French television scientist, who was introduced to us as the French Carl Sagan, wandered around looking for Francophones to interview.

Fortunately a lot of the Canadians could parlez.

The journalists got sufficiently desperate that a couple were even willing to interview a science fiction writer. I gave a lengthy interview to a British camera crew who, however, never got around to asking my name. And I also got interviewed by a print journalist from the island of St. Martin.

If I’d known I was going to be interviewed, I would have had a few things  ready to say. I don’t think I embarassed myself too much, though.

ready to say. I don’t think I embarassed myself too much, though.

By and by someone yelled “First Contact!” I had my camera ready to snap pictures of astronomers going berserk, but unfortunately all they did was peer into their equipment with renewed intensity. I looked at the sun through a mylar filter and, sure enough, there was a little bite taken out of the solar disk right at five o’clock.

So I wandered around and looked at the sun through other people’s telescopes. Kathy had her Astroscan set to project the sun into large flat surfaces, like a piece of paper or a person’s tee shirt, so she was very popular with people who hadn’t brought their own gear, like all the Curaçaoan officials.

The moon crept across the sun’s disk, eating the few sunspots as it went. A pair of cruise ships anchored just offshore, no doubt smashing coral formations with their 3000-ton anchors, the swine. (Cruise ships are evil. Have I mentioned that?) I had thought the eclipse cruises would be farther out to sea, pursuing the track of the centerline, where the eclipse would last its longest, but apparently not.

We had made friends with some of the astronomers, including Louis and Lynn of, I believe, Edmonton. Louis let me use his filter to snap pictures of the sun–for some reason we hadn’t thought to bring mylar along. It grew cooler. The sky grew darker. “Eclipse winds” began to blow– cool irregular gusts, even here in the trade wind belt. Venus appeared in the sky.

The Calgary people had passed out a pamphlet for photographers, giving suggested shutter speeds and ISO settings. They had also strongly suggested that if this was your first eclipse, you not bother with snaps at all, because

you can get so caught up in the details of photography that you forget to look at the eclipse.

This wasn’t exactly my first eclipse, since we’d gone to Mexico in 1991 with Laura and Steve and Bob Norton, but our tour managers bungled it and we got clouded out. What I did was set my camera for totality ahead of time, so that

all I’d have to do was raise the camera and shoot, and not have to think about it.

2:12 approached. Everything got darker. The sun was a thinning crescent. Jupiter, Mars, and Mercury appeared. “Shadow bands” strobed over the earth– it looked as if I were looking at the planet through the blades of a rotating

fan. I looked at the sun through a mylar filter and watched it narrow, narrow . . and then it was gone.

Around me there was a collective gasp, but the filter was black. I’d expected

Around me there was a collective gasp, but the filter was black. I’d expected

to see some special effects. So I dropped the filter, and gaped up at the sun, and I thought to myself,

“Oh my Gawwwwwwwd.”

In the first fifth of a second I understood why people traveled thousands of miles to see these things.

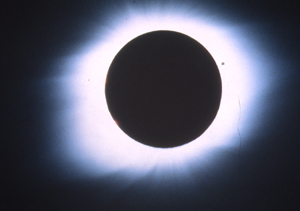

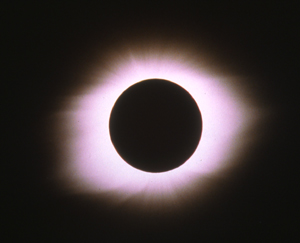

There was this huge silent silver RING in the SKY . It was the most awesome thing I’d ever seen in Nature. The chromosphere had a conspicuous red flare on it. I took a picture.

(Because I was late in dropping my mylar filter, I missed the phenomenon known as “Bartlet’s Beads.” Blast.)

I was very surprised to see that the corona swept out to either side in a single plane, that it wasn’t spherical. (This, I learned later, was because the sun is currently in a quiet phase.) The corona looked as if it were made

up of intertwined filaments, with a very subtle structure. It spread out on either side about three or four sun-diameters, and curled up and down on the ends, like pairs of wings.

I remembered that in the British Museum I’d seen an Assyrian bas-relief showing the sun looking just this way, a winged disk, with the tips of the wings turned both up and down. Apparently an eclipse had passed through

Assyria a few millennia ago.

I snapped pictures. I looked at the sun with the naked eye and through binoculars, through which I could see details of the structure of the corona.

The eclipse lasted three minutes and some seconds. I had my camera primed to take a picture of the “diamond ring effect” at the end of totality, where the sun shines at one end of the ring. I did this, but I snapped a half- second

too early. Blast.

After totality, champagne corks began to pop. We lined up for a group photo. And then most of us piled aboard a bus to head home– after totality, the rest is pretty much an anticlimax, though there were still a fair number of people

who stayed till Fourth Contact, when the moon completely vacated the solar disk.

That night we hopped aboard a boat for a night dive at Tugboat, a site where a boat, which is NOT a tugboat apparently, is sunk in about ten feet of water. We cruised up and down the coral without seeing much– a couple spotted morays was about the sum of it all. The non-tugboat looked much more impressive at night than when I saw it the next day, in sunlight.

Warren, on his first night dive, had some gear problems, and got disoriented in the dark. He decided to return to the boat after ten minutes or so, and bag diving for the rest of the trip. A pity, I thought.

After the night dive we joined the Calgary group at one of the hotel bars for some BBQ and drinks. Peanut sauce on short ribs is pretty much a good idea. Though we’d arrived late, everyone was still high on the eclipse, and babbled

away late into the night.

I began making plans for the next eclipse in Turkey next August. (A trip we never managed to take, alas, though we’ll be attending another solar eclipse in Turkey in March 2006)

2-27-98

“While you’re praying for death . . . ”

The day after the eclipse, Eileen and I went back to sea for a wall dive at a site called Black Rock. There was a high wind, a big surface chop, and a strong current running, and thanks to El Niño the current was running in the wrong direction, messing up the dive plan. We drifted along the reef with the current, barely noticing it, and then had to fight against the current all the way back to the boat. Fighting the current ran my air very low, which I hate to do, less for safety reasons than because it seems unprofessional. It was difficult to get back aboard in the chop, with the stern of the boat rearing up and then threatening to drop onto our heads with every wave.

The corals were very nice, but once again there wasn’t much in the way of fauna. It was depressingly similar to Grand Cayman, except that on Cayman the corals aren’t in particularly good shape, either. I saw no tarpon, only smallish jacks, and the few barracuda were also small. The area had been pretty thoroughly fished out, I imagine by Venezuelans.

The chop had quite a few people seasick during the surface interval. (Not me, I am relieved to report) One poor woman shrugged out of her gear and sprawled on the deck without moving. “While you’re praying for death,” her husband said, “I’ll get your gear ready for the next dive.”

“I’m not diving again!” she said.

“Yes, you are,” he said placidly. And he was right, as it turned out.

Next dive was at Tugboat, where we had dived the previous night. The dive was more rewarding this time, as we saw three morays, including one baby green moray with a head the size of my little finger sticking out of his little

coral crevasse. The critter was almost cute. I also found a pair of flounder doing their flat flounder thing, and a couple scorpionfish, which are something of a hazard as they look very much like rocks and have highly inconvenient eight-inch spines loaded with poison. I wouldn’t have spotted one of them except that it was swimming. Its fins flash bright colors when it swam, a contrast to the greygreen of its skin.

That evening we returned to the eclipse site for some night viewing. I had specifically requested this, since the earlier viewing nights were scheduled against Carnival events. “Assuming that some of us are depraved enough to want to attend Carnival,” I said, “can we go look at stars on Friday night?” And Nicole of Travel Exchange went and rented us a whole bus. This was neat.

Only about a dozen of our Calgary group attended, but there were swarms of astronomers on the site when we got there, mostly from Toronto but including some Germans who accidentally locked their keys in their rented car and thus hitched a ride home with us.

The skyscape was magnificent, clear as crystal. The Southern Cross was a tilted diamond on the horizon. I was able to see a great many nebulae with the naked eye, and made a nuisance of myself asking the astronomers what I was looking at. (“IC-something-or-other,” I was often told.) Eta Carina, the Southern Pleiades, and (rising above the shipping containers at the last minute) Proxima Centauri. Unfortunately the Megallanic Clouds sank with the sun, and we therefore missed them.

I could get used to this, I really could.

2-28-98

“Another Exotic Rum Drink, Please.”

I forgot to mention the previous night’s dinner, which was at Gold Star, a

restaurant that had been recommended to us for good native cuisine. I had

stopa di kabrito, described on the menu as “goat stew.” It should have been “stewed goat,” as the goat meat and the stew had long since parted company. Tender, flavorful, a bit spicy. It was served with a local dish, quite bland, made from steamed corn meal. Not a vegetable in sight. I wished I had ordered a salad along with all the animal protein. Eileen, who had ordered stewed cabbage, came up with a winner: sweet, spicy, with flavorful chunks of meat.

After we walked back to our hotel, some of our friends asked us where we’d

gone. “You walked to the Gold Star?” they asked us in horror. Apparently

it’s in a bad neighborhood, though it looked middle-class enough to use, with those Dutch lace curtains in the windows.

“The worst they would have done is take your money at gunpoint,” we were told.”They probably wouldn’t have shot you.”

Comforting, that.

By Saturday the 28th, our last day, the tropics had really got to us. The long walk from our room to the dive pier was getting longer and longer. Eileen dropped out of the diving, so I went alone.

Fortunately the highly stimulating Vivienne was our divemistress this time out, which gave me a place to rest my weary eyes when I wasn’t under water.

The first dive was a drift dive that took us through three dive sites, of which I only caught the middle one: Kathy’s Garden. My dive buddy, who I’d just met for the first time, was a little flaky. Went down ‘wayyyy deep, much

deeper than we’d agreed. He’d never done a drift dive before, and hadn’t realized that you’re just supposed to drift with the current (which was quite fast), so he was kicking along and moving very, very, very fast, with the reef soaring by so quickly that I really didn’t have time to look for goodies. Toward the end of the dive, the reef made a turn, and the current started carrying us down and away, into the chasm, a fact I only discovered when I looked at my gauges and discovered I’d been carried to 82 feet, from my self-imposed limit of 60! “Dive the reef, not the chasm” has always been my motto. It was a hard slog into the current to get back to our boat.

Below the boat, on the flat part of the reef, I saw a couple fish of a type I’d never seen before. They were squat, grey-brown things, with a broad head, just sitting on the sand. Maybe 12-14 inches long. They were strongly reminiscent of the scorpion fish, except that they weren’t, lacking (insofar as I was willing to investigate) the poisonous spines. I checked in my fish guides and didn’t find them.

Our surface interval was spent cruising the Spanish Water, one of the island’s many inland lagoons. The most famous of these is Willemstad, but there are a number of others. The Spanish Water is full of little mazy inlets, peninsulae, and small islands, all of which are rapidly becoming occupied by luxury villas and private piers. They all looked very nice. I’d guess they each ran $3-5 million, many with a less-than-charming view of the sandstone quarry.

Our last dive was a place called the Ledges, the all-too-usual combination of lovely corals– some very nice elkhorn coral on this island, by the way– and very little in the way of large or interesting fish. A large green moray was

turned up. A series of ledges at 25-30 feet swarmed with small fish and a large number of drumfish, which are weird prehistoric-looking things, hard to describe except that they look like an animated lozenge with a pair of kissy-

lips at one end and a tiny tail at the other.

After lunch and siesta, the four of us went out on the town, and wandered about Willemstad. We crossed Queen Emma’s Bridge to Otrabanda, on the far side of the ship canal, and found out where the poor people lived. It was a little too reminiscent of an inner-city slum for comfort, so we wandered back to the channel and drank beer in a sidewalk cafe while watching the sunset play on the Caribbean colors of Punda. Then we crossed back over the bridge and wandered about, hoping to find a place to hear island music. The choice seemed to be between ear-splitting highly-amped jazz in a sidewalk restaurant, or AOR Top-100 hits at the Hard Rock Cafe Society, a club that will last just as it takes for a real Hard Rock Cafe to open on the island.

I really would have liked to have danced to tumba, or at the very least to some Latino stuff. No doubt I could have found it if I’d known where to look. All those bands in the Carnival parade must play more than once a year. But

it wasn’t on, so we returned to the Grill King for exotic rum drinks and dinner. Warren and I switched dishes from our last visit: he had the ribs in black bean sauce, I had the wonderful grilled shrimp.

There didn’t seem to be much night life going on– one is reminded of the Dutch influence, I guess– so we headed back to the hotel.

You don’t want to read about the return trip, the tiny airline seats, the baggage that had grown so much heavier in the last week, the perpetual stampede at Miami International, which has to be one of the world’s worst big

airports. The few remainders of the Calgary Group had a big dinner together in Miami the last night, fourteen of us at a big table at a restaurant called Victoria Station, made up of old railroad cars hooked together. The margaritas were served in big 16-ounce tumblers. The food was pretty good. The waitress was patient.

And then, the next day, home, where Steve and Laura kindly picked us up and fed us dinner. Kathy had got the flu. I had got a tan.

I’m so good at compulsively having fun on a trip that when I come back from vacation I’m usually on the point of exhaustion, good for nothing but sleep, but this time I actually seem to have had a vacation that sent me home fairly

rested.

I was ready for another adventure.